Those were the warning words of the Libyan Pulitzer prized author, Hisham Matar, to a mesmerized public at the American Library in Paris this freezing January evening. His book The Return had just been translated into French.

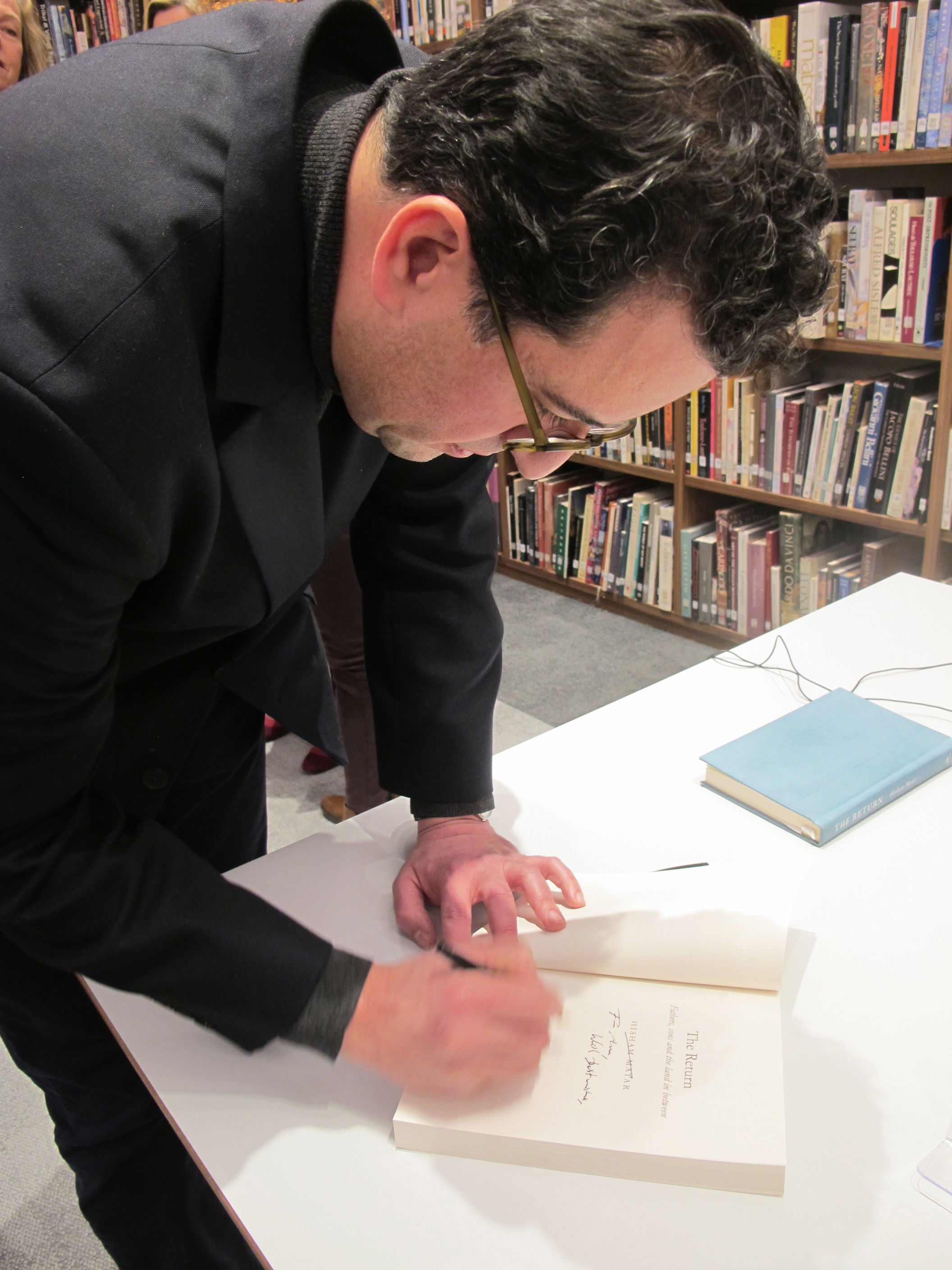

Hisham Matar signing his book

The danger with dictators

The book is an auto-biography about a search of a son for his lost father under one of the world’s worst dictators: Muammar el-Gaddafi. The author, Hisham Matar, born in 1970 in New York but mostly grown up in Libya and in Egypt lives in London and writes in English. In the Country of Men, his debut novel, was shortlisted for the 2006 Man Booker Prize. His next novel The Anatomy of a Disappearance was published in 2011. His essays have appeared in prestigious international newspapers such as The Guardian and The New York Times.

Father and son

His father worked for the UN but was then accused by Gaddafi to be in opposition and had to flee his homeland in 1979. The family lived in exile in Cairo, Egypt, were the children attended school. Hisham then continued his studies, in architecture, in London where he settled. In 1990, his father was kidnapped in Cairo and taken to the much feared Abu Salim prison in Tripoli, Libya. Since then his son has been searching for him. This thrilling and yet so heart-breaking auto-biography is about this search. Is it the search of his father, his nationality, his culture or Hisham’s own identity? Those were some of the questions he tried to answer in this interview as well as in his book.

Why did you decide to switch from writing novels to write such a highly auto-biography?

– It wasn’t really a choice but more of a process. Upon my return to Libya after the revolution to try to find my father, I started also to journal. I interviewed among others, former prisoners who had met him or heard of him because he was contained in an isolated cell. Afterwards, I couldn’t write at all for several months, not even an article. I thought that I had completely exhausted my writing.

So how did the book come about?

– I took along my journal and traveled to a friend in Italy. I tried to read it as if somebody else had written it. Then more memories surged and I wrote them down. It developed into an article that I sent to my editor who asked me to write another one and then another…

Your story is highly personal yet it reaches an international audience. How come do you think?

– Relationships between father and son are universal. If you don’t have a father to revolt against, you can’t find your own identity. If you don’t have a nation, you don’t know which culture you belong to. These are questions without borders. It’s the reactions to what happens to us that create the individuals we become.

In what language did you write originally? In English or in Arabic?

– I wrote in English even if some were translations from my Arabic interviews. However for me, all literature is translations – or interpretations – of our feelings. Some authors only have one language, others two or several but it’s the choice of words to describe an emotion that’s essential and not the language used. However silence is as important. It’s not the same silence if you sit alone in a car or with a sleeping child next to you for example. That feeling must also be transmuted into words.

Observation is thus paramount to writing?

– It’s the essence! I learned that as an architect student. My teacher made me go outside and draw a tree for three hours which seemed like an eternity at that age but it formed me into observing and transmuting.

Was it difficult to write such a personal book?

– I’m a private person so it wasn’t easy. It was an eternal fight between me personally and the author in me but the latter got the upper hand. The author demanded more and more of me, was curious and smooth at the same time. I had to hang on … Books are destiny. I don’t choose my books, they choose me. The joy comes afterwards when the struggle is over and I see the end result.

Now you’re back in Paris where your writing started. How does that feel?

– I was here between 2001 and 2003 and decided then to write full-time. It’s nice to be back to this beautiful and inspiring city – especially now when my book has been translated into French.

The widely popular author then rushed away to his next meeting. I walked home, wondering about the similarity between Middle Eastern dictators and military regimes and our Western future. Can writers and philosophers really make a difference in our world’s development?

Maybe not but what they can do is describe the truth – even if only a personal truth – and through research and openness make it harder for dictators to hide their unlawful behaviors. Therefore freedom to create and speak out is paramount for the development of humanity.