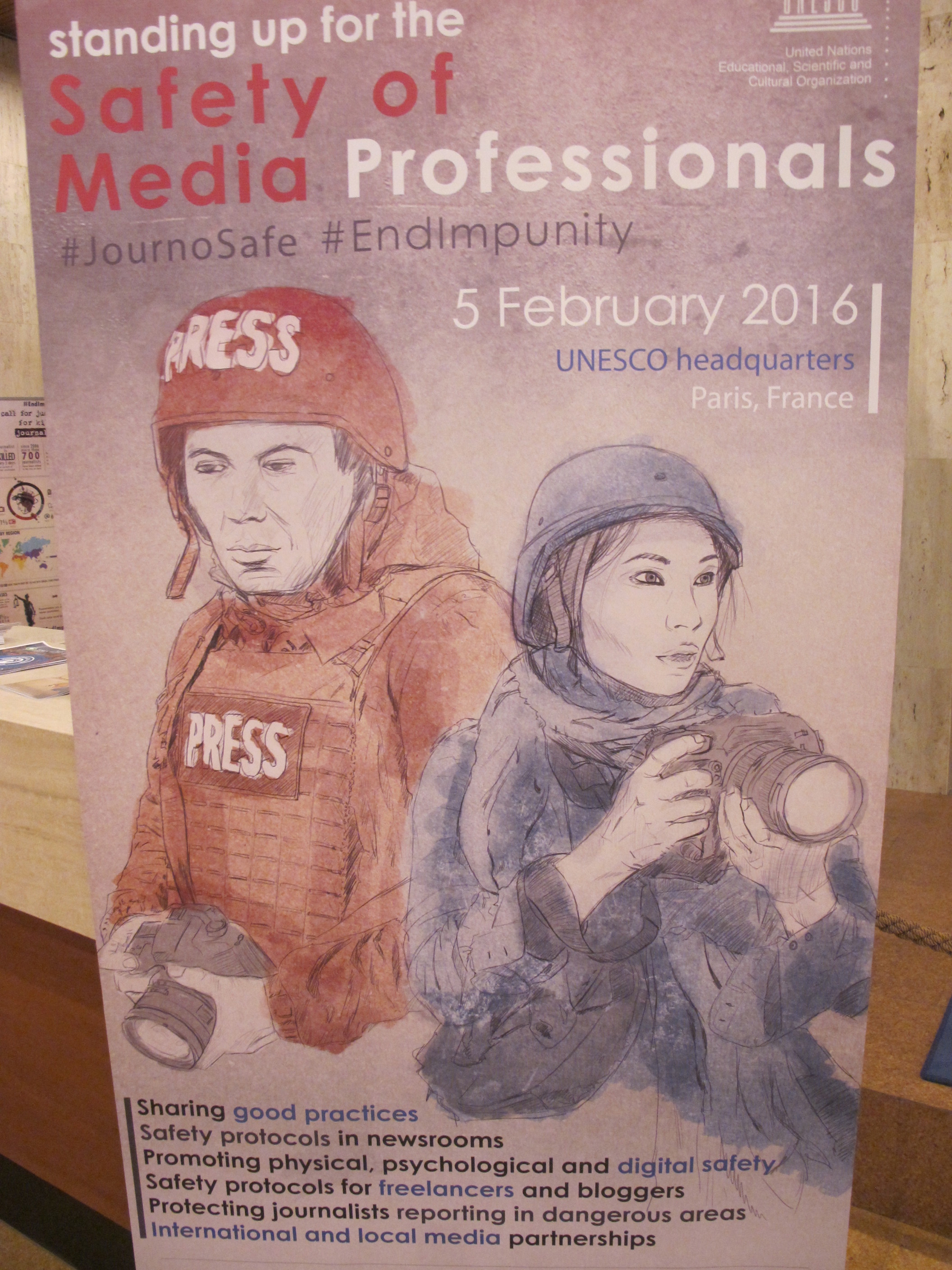

An international conference about the safety of journalists was held at UNESCO, in Paris, on 5 February 2016. They are kidnapped, attacked and murdered on a scale never seen before. To show a press card isn’t a guarantee anymore, rather the opposite. What are the security measures available? That was the question of the day.

UNESCO:

The conference started with speakers from the larger media organisations, such as CNN with the well-known reporter, Christiane Amanpour and Washington Post’s editor Doug Jehl and Diane Foley’s – who’s freelancing son was beheaded by Daesh – touching speech. She’s founded an organisation for the security of freelancers whom are often more at risk than employed journalists.

Zaffar Abbas, an editor from a major Pakistani paper, explained that, in his country, since the press has become relatively free, other means are being used to quite down uncomfortable reporters. The phenomenon has reached such peaks that several media organisations that usually compete with each other, have decided to cooperate. If a member of the media staff is killed or attacked, somebody else makes sure that the story comes out. Admittedly, the most exposed journalists are the locals who can’t move or leave once their article has been published.

From Latin America, Ricardo Trotti, described how many media-related crimes are linked to the mafia and drug-business. He asked for the courts to take these assassins to court, which they are reluctant to do. South African M. Mkhabela complained about police brutality in his country.

Before closing for lunch, Solomon Passy, former Bulgarian Foreign Minister, held a hopeful speech about an SOS-App that is being studied but needs sponsors.

Diane Foley

During lunch-break, I met a Syrian reporter who is currently stationed in Cyprus but has contact with reporters inside Syria who risk their lives daily. I also met a desperate young Afghan reporter who explained that “several of my colleagues have been murdered by Talibans while Western media is only concentrated on Daesh.” Another colleague from Yemen was desolate that no foreign journalists came to his country to report of the dire situation there. “Maybe we could if we’d get proper protection”, I answered him because of course information from such places is essential.

Christiane Amanpour

Reporters without Borders:

There were tables all around displaying brochures and books. One of those was Reporters without Borders who gave out (together with UNESCO) safety guidebooks for journalists in all major languages “to keep in your pocket or inside your head” as it said on the first page. Information is essential or as the war photographer Robert Capa put it: “Dead men have indeed died in vain if live men refuse to look at them”.

Reporters without Borders, Christophe Deloire

However what happens when the messenger is killed? I read that during 2015, 67 journalists and media workers have been killed, amongst whom one-third in so-called “peace-zones”. The free word evidently isn’t that free in all countries. The UN Secretary General, Ban Ki Moon, talked about the failure to protect media workers and about his concern for the increase of violence against reporters.

Not many journalists though, especially not freelancers, are aware that Reporters without Borders lend out helmets, goggles, bullet-proof vests, have a SOS-number and give special training. All this is relatively new to us reporting from dangerous places. It would have been welcome when I was for example in Tahrir during the revolution, witnessing how snipers, placed on roof tops around the square, were shooting people in the eyes, when the potent American-made teargas poured in from the side-streets and gangs of rapists were terrifying women around the corner (a system apparently implemented during the last government and widely used by the Muslim Brotherhood’s radical members to force women to silence and hindering them from taking part in any demonstrations).

More than 750 journalists have been killed during 2005 while exercising their profession or as a result of their reporting. Reporters without Borders gave out maps of the world’s most dangerous places for journalists. Not surprising, Syria, Yemen, China, Saudi Arabia, Iran and a few others topple the list. Russia, the Middle Eastern countries and Mexico follow tightly behind. In some countries human lives don’t seem to be worth much.

If one survives as a reporter it’s a matter of chance. Or is it? According to this excellent guidebook, several preventive measures can be followed. It’s essential to be well prepared before hitting out on a mission in potentially dangerous zones. To leave once mobile number to the Embassy, friends, family, colleagues is one way, and another is being accompanied by a local fixer who can translate and who understands the cultural and social codes.

After lunch we were separated into groups depending on themes. I choose the one about freelancers.

Safety for freelancers:

The situation is dire for many freelancers who aren’t employed by a specific media organisation. As resources are on the decline, that group is gaining in momentum. Sponsorship to independent papers is also minimal and without resources, there is no safety training either.

Without local reporters we can’t grasp the situation in certain zones however. Salim Amin, from A24 Media in Kenya, told horrific stories of local freelancers being arrested or murdered while exercising their job. They are often young, inexperienced reporters in dire need of money, so they take risks in order to get a story, hoping for a scoop, hitting out to dangerous places without being well prepared. However even experienced reporters aren’t always safe, as the tragic death of our Swedish colleague, Nils Horner, murdered in cold blood on a street in Kabul, proved. The assassins are seldom caught or tried, on the contrary, in several dictatorships it’s part of the system to “silence to messenger”. Free media isn’t appreciated everywhere.

Some hope was however instilled in the audience this otherwise rather gloomy day. A helpful institution, ACOS (A Culture of Safety), was founded in February 2015 for the safely of freelancers and their “safety principles”. Another association helping freelancers is Rory Peck Trust (https://rorypecktrust.org ) based in the UK whose program leader is Elisabet Cantenys.

What wasn’t really touched upon though, was the safety of the fixers – all those locals helping journalists on assignment. One sad example is the academic and freelancer Guilio Regeni, murdered in Egypt (his tortured body was found in a ditch on 3 February 2016) probably because he refused to give away the names of the local activists he was researching for his PhD. It’s always easier to spy on foreigners and through them localise “disturbing” inhabitants. It’s an old trick inexperienced foreigners aren’t always aware of. To take care of the fixer is also a responsibility journalists have.

Security for women reporters:

Another issue that was just touched upon were safety issues for female journalists. There were several women speakers and journalists though. Information was available also, such as OSCE’s report about “Countering Online Abuse of Female Journalists” and the guidebook has a special chapter dedicated to the subject. The book No Woman’s Land, on the frontline with female reporters (International News Safety Institute) was also for sale.

There is a bright side to being a woman though and that’s our advantage over male colleagues to easier interview women and children at least in parts of the world. We also tend to have another interest in these groups and can therefore offer them a voice. It’s therefore essential that women’s safety be taken into consideration even in war-zones because we report information that differs in its content.

Freelancing women are especially at risk and nowadays we have to be both photographers and interviewers that hinder us from keeping a watchful eye out for ourselves. It’s essential to be escorted by a male colleague or a local fixer.

As the conference came to a conclusion, we were asked to spread the information: “not only for the sake of journalists but for the sake of freedom of expression, because without reporters there is no possibility for democracy”. Who else but passionate journalists would risk their lives to reveal the truth?

Anne Edelstam, Paris