Women promoting peace: visions and actions. During this conference for “women and change” hosted by the Human Foundation and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, there were several interesting speakers. My contribution is was follows:

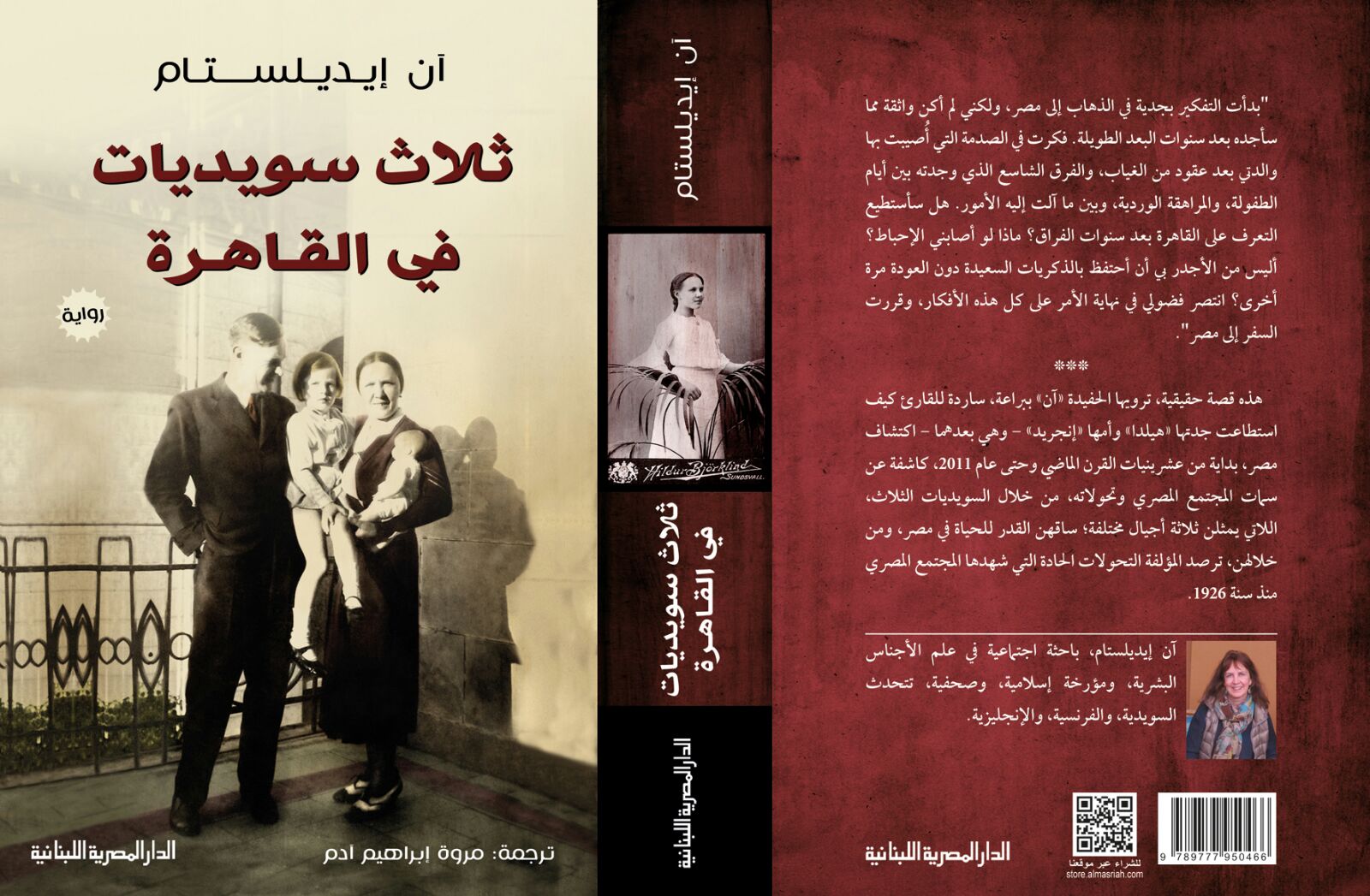

I believe that telling our unique stories is a way to promote peace. I want to share during this talk my family’s cross-cultural and cross-generational saga – Three Ladies in Cairo – that starts with my great grandmother in Northern Sweden at the end of the 19th century and ends with me in Cairo in June 2012.

The idea behind this story is to show the impact of cultural exchange and the importance of our collaboration throughout generations, different cultures, traditions, religions and historical time settings. We need to start telling stories again and listen to our ancestors. By learning from our grandmothers’ accomplishments we can feel empowered to continue the struggle for women and for peace.

I originate from a lineage of adventurous and strong women who dared to take a step into the unknown.

My grandmother, Hilda, came from the North of Sweden, a coastal town that used to be very prosperous at the turn of last century, called Sundsvall. There she met my grandfather, Torsten Salén, who was to be appointed judge at the Mixed Courts in Egypt in 1926. These courts were there to judge foreigners who had law-cases connected to Egyptians or business in Egypt. Hilda dared to leave her comfort zone behind and took the boat with all her belongings and sailed to Africa to be reunited with the love of her life. She is a continual inspiration for me whenever I feel nervous about setting my foot in a strange environment to cover a story for my paper. We do need role models. Look for them in your family and around you. They exist everywhere and are the silent heroes the world abounds in.

My grandmother was quite an emancipated woman, one of the first to wear trousers while skiing instead of the customary long skirt (!), helping her father who was the town doctor, as a nurse, before her marriage and then turning to photography, which has also been my passion since I was a child. She was a curious person with a keen interest in women’s rights, her own mother having been an example of independent and hard working woman for her. She befriended Hoda Sharaawi the first or at least the most well-known Egyptian suffragette.

Here is an extract from my book Three Ladies in Cairo about that encounter:

Not everything was rosy in Egypt, though. One of the problems was the situation of the Egyptian women. Not all of Hilda’s friends were from well-off families. Many Egyptian women, she realised, had to cope with what seemed to her insurmountable problems. Some of those women were quite involved in politics though, such as Hoda Shaarawi, who fought for the development of her illiterate sisters. She became known as one of the most famous feminists of the early twentieth century. Hilda came to admire her greatly for the courage and integrity behind her charming smile and elegant manners.

They first met at a dinner party with some of Torsten’s colleagues, where they immediately took a liking to each other, and they came to spend many interesting hours in each other’s company after that initial meeting. Both were freedom lovers and independent women in their own right. Hilda was impressed by her new friend’s deep knowledge of her country, imposing manners, and the precious insights into Egypt that Hoda gave her. But she was also an example to Hilda.

A few years before, in 1923, Hoda – an elegant woman from the Egyptian aristocracy, herself part of a harem – arrived at Cairo’s railway station and was greeted by her fellow Egyptians. She was already known as a feminist then and was returning from an international woman’s conference in Rome. “It’s now or never. I have to do it! Hoda, you can do it, just do it now!” She convinced herself to do the unthinkable.

Standing in full view of everyone, she slowly removed the veil covering her face, feeling the onlookers catching their breath. “Now it’s too late, it’s finally done”, she thought. Some followed her example then and there. “Kefayya, kefayya!” – enough, enough! – women were shouting. That was the beginning of the end for the harem system in Egypt.

“But some women are veiled, some aren’t, seemingly regardless of their religion, it’s all a mystery to me,” said Hilda.

“In the countryside, women have always worked alongside the men, since time immemorial, and have never been veiled,” Hoda explained. “But poorer city-women do put on a veil when they go out. Otherwise, it’s a class matter. The aristocratic women were veiled to distinguish themselves from the slaves, who weren’t. And it’s considered chic to be as white as possible, you see, because that proves that the husband works enough for the wife not to have to. One of the safest ways to keep the skin out of the sun is a veil.”

“In Sweden, we don’t have that problem. The long winters see to that!”

Rather than being religious, then, the veil and the harem or women’s quarters represented social and financial etiquette. The men’s honour depended on the women’s chastity, so keeping them segregated was a way of keeping their honour safe. In the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, the women in town, whether Jewish, Christian or Muslim, were generally veiled. It was a regional custom and not a particular religious symbol – after all, as Hoda pointed out, the headscarf wasn’t even mentioned in the Koran.

“We have Mohammed Ali to thank for the country’s opening towards the West and its customs,” she said.

As M. Ali introduced new technology into the country and modernised it, Europeans flooded in. It started with men, experts in different technical domains; then their wives followed suit; followed by governesses and teachers. The European women’s ideas and thoughts about emancipation were gradually transmitted to their Egyptian sisters.

“The Egyptian elite also started to travel to Europe. We behave like you there and remove our veils and socialise with men. But as soon as we return home, we wear the veil again and go back to the old traditions.”

“The return must be ever so frustrating then!” said Hilda.

“Yes, exactly. That’s why I did what I did.”

From that deliberately shocking act at the railway station, a definite breach had been opened.

The feminist movement in Egypt hadn’t started as such but as part of a general movement against the colonialists. Women and men fought side by side against their common enemy and women’s emancipation in Egypt began with the elite. “I became interested in Wafd, the Egyptian political party created to fight the colonialists. Then, I started its female counterpart. It was quite a challenge for a woman to do,” she said. “But we were so fed up with being told what to do that it was quite easy to recruit people. At first it was to help our men get rid of the colonisers, but then we realised that we enjoyed feeling empowered.”

From 1924 to her death in 1947, Hoda presided over the Feminist Union, an Egyptian feminist movement, which she financed herself. At first, its members derived from the upper classes, but the middle classes soon followed. It published two monthly magazines, one in French and the other in Arabic; it set up a clinic for poor mothers and their infants, workshops, and care centres for working mothers’ children. A secondary school for girls opened in 1924 and before the end of the decade, women were accepted at the university.

“That’s a new phenomenon in Egypt,” Hoda admitted.

“Well, you certainly had to face many obstacles to get where you are!” said Hilda.

The Saléns stayed on in Egypt during WWII and left the country, after an additional three years in the Upper Courts in Alexandria, in 1949 when the Mixed Courts where closed to become entirely Egyptian. They thus didn’t live through Nasser’s nationalisations and the expulsion of the King and of the foreign communities from 1952 until his death in 1970. He turned Egypt into an all-Egyptian nation.

In 1975 my father was appointed Swedish Ambassador to Egypt and the family moved to Cairo. After my French Baccalauréat, I started studying at the American University of Cairo. I stayed on there, studying, traveling and working until the mid-80s when I married and moved to Paris. Despite my love for Egypt, I also discovered fundamentalism that had been lurking under the surface since 1928 and the beginning of the Muslim Brotherhood.

My connection with Egypt was interrupted because of small children and a busy family life.

Then 9/11 2001 in New York happened and a veritable “Islamophobia” overwhelmed Western media. I decided to go back to rediscover “my country by adoption”.

These past ten years, I’ve been traveling there on a regular basis as a journalist, reconnecting with my Egyptian friends and interviewing numerous Egyptian women and men. Internet has exploded in Egypt and connection has made wonders to encourage people to share and spread ideas.

As a journalist and a woman my experience is that we write and angle our stories differently than men’s. It’s important therefore that we feel safe and supported in our work, as journalism has become a high-risk job. Especially independent media plays an important role in exposing information that many leaders and corporations want to keep silent about. However it’s also our responsibility not to dwell in horror stories or images but to offer hope for a better future. I believe that women can be at the forefront of peace-journalism.

By building bridges between the West and the East, we promote peace by creating together a new vision of a more sustainable world. It’s only through understanding each other and seeing the common traits we all share while celebrating our uniqueness that we can hope for peace. There seems to be a global force that drives us all towards the same goals: a clean planet, safety for our children and respect for each other. It is there bubbling up slowly but surely to the surface and gaining in momentum. We mustn’t be discouraged on our route but keep the sail well directed towards our goals. Therefore we need to connect and encourage each other.

Just as Hoda Sharaawi once stood up for her Western sisters, so it’s time for us now to stand up for our Middle Eastern sisters who still suffer, independently of religion, under the yoke of a patriarchal society. Peace in this world will only be achieved through a just balance between the masculine and the feminine and to realize that we women have to make our voices heard. It’s time to speak up girls! Our mother earth – as Mary Robinson called our planet during the COP21 in respect of the indigenous peoples – needs us desperately. It’s time to put our natural shyness at side and become much more active in our mutual collaboration and support, both locally and internationally, to counteract the dark sides of patriarchy such as wars and destruction.

I met my Egyptian translator, Marwa Adam through Voices of Women Worldwide (VOWW). Our collaboration is but one example of how we can and should cooperate cross-generationally and cross-culturally to generate a positive future. I strongly urge you all to become part of our global sisterhood by joining VOWW – it’s an entirely free forum – cooperating with other women movements around the globe to shine your uniqueness in togetherness!

At the Swedish Institute