This passionate couple’s life is impossible to dissociate from each other. Their works of art are exhibited side by side at the Orangerie in Paris until mid-January 2014. The rather dormant museum has undergone a recent face-lift and it reopened its doors with bravura!

One of Diego’s murals

Passionate love:

Is often associated with pain and Frida Kahlo (1907-54) personified just that. Suffering is probably the main characteristic of this Mexican woman who painted her story in a frenetic way with maybe the futile hope of getting some relief through her art. Her deeply tragic life wasn’t made any easier by her beloved husband’s, Diego Rivera (1886-1957) continuous unfaithfulness with among others her own sister! The couple was nicknamed: “the elephant and the dove”…

However he helped her in her career as a renowned artist. Some of his great murals as well as paintings and lithographs are displayed in this interesting exhibition. The Mexican art-school is also revealed through these two artists with works of arts using the Mexican culture as background with its life cycles, revolutions, religions, myths, traditions, workers and farmers…

Diego Rivera’s European tour:

The same year Frida was born, the twenty-year older man arrived in Europe and stayed there for nearly fifteen years. Helped by funds from the Mexican state, he could study art in Madrid, Paris, London and Brussels. Diego befriended among others Picasso, Mondrian, Léger and the Russian Zadkin. His meeting with Juan Gris in 1914 led him to paint “synthetic cubism” using a unique palette.

He exhibited in Paris and New York before his trip to Italy and the encounter with the frescoes there that would eventually inspire his murals once he moved back to Mexico in 1921. Two years later he met Frida Kahlo and they married in 1929.

One of Diego’s early, cubic paintings

Diego Rivera revolutionized art in Mexico with his murals. His symbolic and epic paintings transformed the history of his country into a modern myth. The Department of Education encouraged his frescoes’ paintings and gave him the financial means he needed, believing it was art available for all (similar to today’s street art).

In 1922, his first large mural was finished in the same university where Frida was studying medicine and they fell in love. He made his real brake-through with the 1600 m2 mural called the ”revolution’s ballad” – in honour of the workers and of the indigenous Indians – showing Frida distributing arms. In some of his frescoes he painted harmony between man and nature.

Even in the USA (1930-34 and 1940) he painted some revolutionary frescoes with original ideas about industry and technology. In Detroit, he became fascinated by Ford’s industries and even got an order from the Detroit Institute of Arts. However the painting of Lenin at the Rockefeller Centre in New York was less appreciated…

Rivera’s frescoes inspired an entire generation American artists and are at the heart of his works together with his political ideals.

The art couple:

Rivera’s gigantic historical frescoes are in sharp contrast to Frida’s much smaller, personal and autobiographical paintings.

Despite that, the two artists met in their Mexican cultural identity synthesizing the post-revolutionary country. Diego awakened Frida’s interest for the indigenous farmers mixed with pre-Columbian culture. The sun and the moon are two important factors in the ancient myths that are recurrent themes in Frida’s works. It was mostly to seduce her husband though that Frida made several self-portraits dressed in typical Indian clothes and jewellery.

The couple also honoured life in general in their paintings rich with symbolism and passion. Their art is impregnated with animism and the Mexican flora and fauna are intimately associated with the cycles of life and death. Their personal story thus transforms itself into mythical sagas.

Frida Kahlo:

Said that she had had two accidents in her life: the bus accident and Diego… Already as a young girl she got polio and only 18 years old she had a devastating bus accident where her spine was crushed. Operations and hospitalizations became part of her life from then on. Maybe it wasn’t so strange that she wanted to become a doctor before switching to an artist?

Frida’s original portrait of Luther Burbank

Due to her weak health, she couldn’t have any children, a tragic reality. Her three miscarriages are exhibited in painfully realistically depicted paintings. Other paintings show her suffering carrying tight corsets she was forced to wear before she was definitely confined, from 1950, to a wheelchair. Added to her physical pain was her passion for Diego with his notorious unfaithfulness.

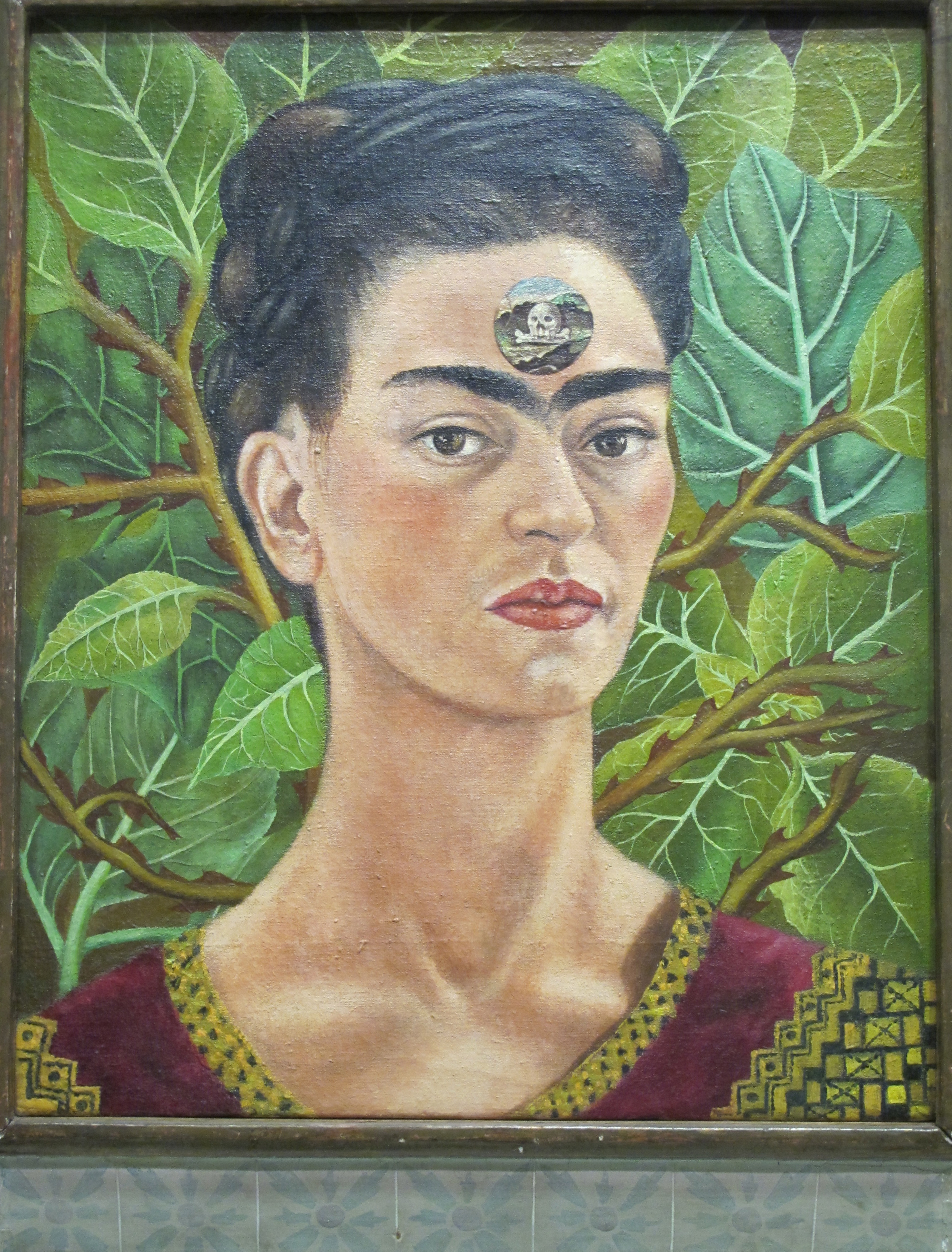

She painted mostly from her bed in her “blue house” in Coyoacan as it was there that she spent most of her time. With the help of a mirror, she made self-portraits where nothing escaped her vigilant and truthful eye. The beholder is invited into her world filled with pain, we live with it, we feel it, we engage in it… that’s what makes her art so alive and raw without ever being vulgar or voyeuristic.

Frida makes herself into an icon, inspired by the small Mexican portraits of Jesus, Maria and the Christian martyrs painted on metal that the Mexicans like to wear or carry along in their pockets. Her intensive eyes follow the observer. Her works of art are considered some the 20-th century’s most interesting and I couldn’t but agree.

Icon:

Frida Kahlo has become a star in the art world – nearly like a pop star – since the 80:s and especially these past years. Latin America’s most famous artist can pride herself to have transmuted into an international, revolutionary and passionate popular emblem. Her Mexican clothes have inspired fashion designers and her unibrow is displayed on more or less kitsch objects as a symbol.

Her capacity to transform pain into art and her intimate life to a universal message make her a modern icon. Women’s suffering get a voice through Frida’s art.

While Frida Kahlo lives on in our hearts, the man who facilitated for her to become a famous artist nowadays feels out-dated. Diego’s frescoes with socialistic themes don’t carry the feeling about them that Frida’s art exhumes. They are merely decorations or historical illustrations without much depth or sensitivity.

I felt like taking Frida in my arms comforting her, saying: “he isn’t worth all your pain, you have so much more to give your contemporaries than he has!” I hope that she can see us from wherever her soul is and take consolation in knowing how much she’s admired and loved now by both men and women.

Anne Edelstam, Paris