Several books have come out lately analysing the IS/Daesh phenomenon back and forth. However a recent one – albeit in Swedish – gives another angle to the problem, as I’ll present it here.

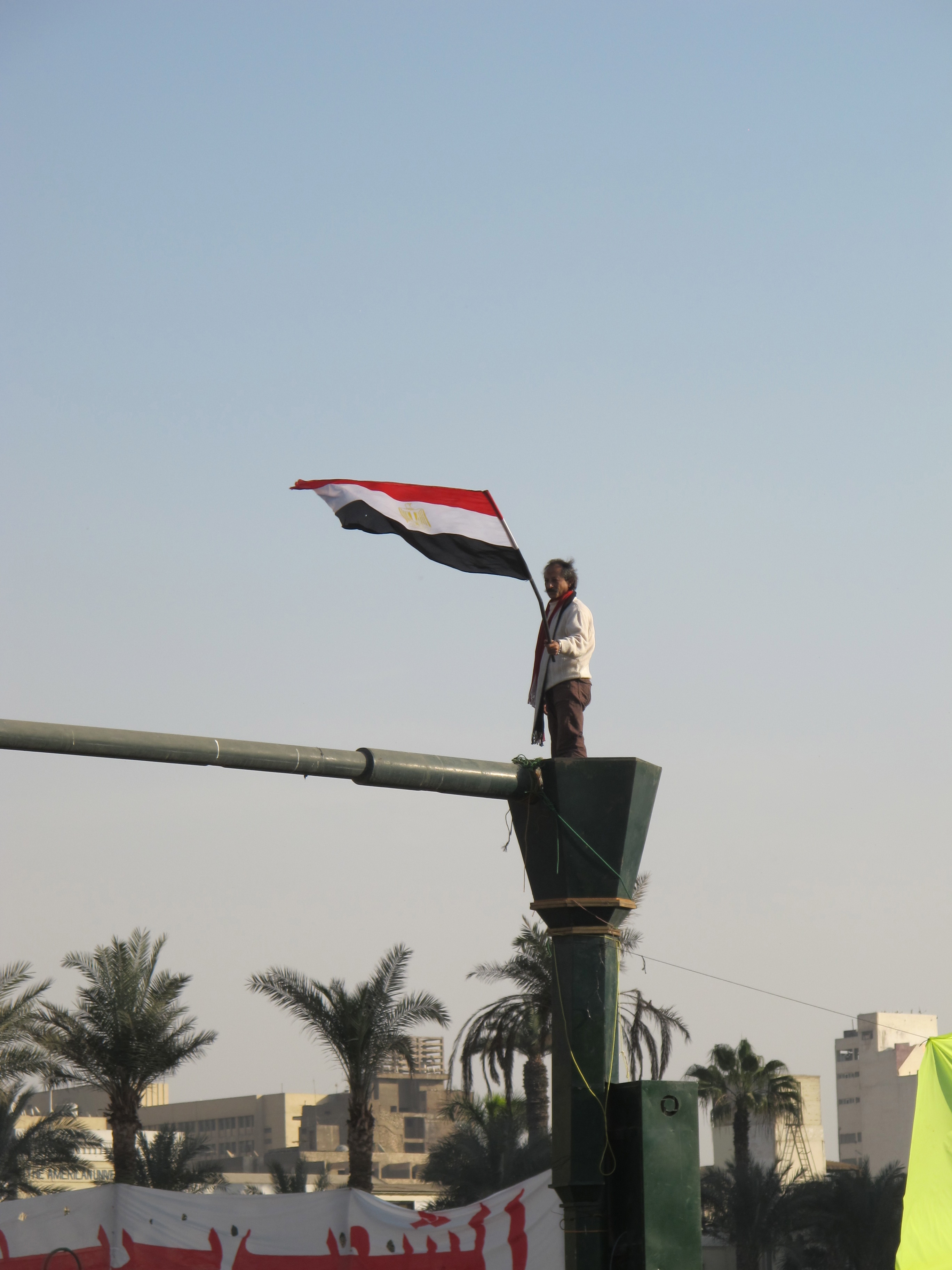

The Arab Spring, Tahrir Square

Invitation to a road of peace:

Four authors among whom Bitte Hammargren– one of Sweden’s most esteemed Middle Eastern journalists – have contributed to this book (Ickevåldets vägar, Fred I terrorns tid). To read about peace is a welcome subject in this time of terror threats, escalating violence, ID-searches, security checks and a general increase of paranoia. This study gives the reader a somewhat hopeful image of the incredibly complex and dangerous situation the world is currently facing.

“Kidnapped” revolutions:

Different historical events are cited as examples where non-violent revolutions led to radical societal changes and others where they, on the contrary, led to increased repressions against government opponents.

The Middle East, after the “Arab spring” is but one example of non-violent revolutions that haven’t succeeded in making societal changes (except maybe for Tunisia) for the better but rather the reverse.

In order to understand why non-violence sometimes isn’t enough, the author, Isak Svensson, differentiates between what he calls “principal” and “pragmatic” non-violence. Openness for dialogue and consideration of the opponents has been missing in the current non-violent revolutions – in contrast to for example Gandhi’s fight against the British, according to him. The “Facebook-revolutions” we recently have witnessed lacked political leaders who could take over command once the masses were mobilized. Instead they left a gap external forces easily could fill. As such, these non-violent revolutions (both in the Arab world and in other places such as Ukraine) were instead “kidnapped” by power-hungry agents. Because of a lack of dialog and leadership, the uprisings instead led to increased polarisations and societal split.

The Swedish peace-movement is trying to build strong societies that lessen rivalries between different groups and states. Isak means that we have to try to focus on the long perspectives and support peace-initiators and activists, because even if parts of the world are in turmoil, organized violence per se has diminished.

Need for justice:

Ms Hammargren insists on the need for justice and equality for peace to prevail. She criticises both Western military industry with its weapon exports and rearmament, of amongst others Saudi Arabia, as well as its support of dictators. She also lists several common factors that push people onto the streets: such as, the lack of freedom, high youth unemployment, patriarchal structures, disregard for women’s basic rights, corruption and export of Wahhabism and Salafism. I’d like to add a lack of family planning that has led to an explosive boom of the population and an increased antagonism between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

The journalist then analyses actual situations from Bahrain, to Syria, via Iraq, Egypt and Palestine. She reminds the reader of that in 2017 there will be one hundred years since the Balfour-declaration – when Great Britain promised the Jews a national home in Palestine – was signed and soon also fifty years since the occupation of the West-bank and Gaza started.

After having cited several peace-activists and their struggle against fundamentalism, she ends her chapter saying that real reforms are needed otherwise we can expect many more uprisings. The international community’s role is essential in combatting authoritarian regimes with non-violent methods through well-organised civilian opposition. “Maybe however the oil-economies first have to implode before we can expect a peaceful reform in the Middle East” (my translation from Swedish). Well, hand in hand with her statement, goes the “green wave” with what that implies of increased sustainable energies as well as trying to halt the climate changes we’re already witnessing.

“Religion and violence”:

Joel Halldorf, in his chapter, tries to contradict the general statement that religion is a source of violence. He affirms that the worst conflicts haven’t started because of religion and that the world’s religions don’t really have a common denominator. The worlds’ religions are also intimately linked to social, everyday and historical events. Hence they cannot be studied outside of these frameworks.

However, Joel states, some religions have been “corrupted” by dictatorial leaders who demand their members’ total obedience and pretend to detain the absolute truth – or “God’s edict” – as excuse for their behaviours. He then adds that some “religious fanatics” have themselves been oppressed and can therefore also be classified as victims. He gives some examples such as Jehovas’ Witness who were persecuted during WWII but he omits to say that the organisation doesn’t refrain from using both physical as well as psychological violence against the members who don’t accept their rules, as several ex-members have witnessed.

According to early Church orders, it was forbidden for a Christian to be a soldier. The Church was supposed to be pacific and wanted to restrict violence. He doesn’t mention the inquisition or the Church’s mercilessness in the forced conversions of many indigenous populations though.

Islam – as practiced by over a billion people – doesn’t lead to violent behaviour either according to the author’s analysis. One cannot generalize over lesser terror-groups such as el Qaida or Daesh. In the Middle East, it was rather secular politicians such as Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Iran’s Shah Reza Pahlavi or Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser who brutally oppressed their religious opponents in their respective countries.

As opposed to Western countries, where modernity and secularity have slowly sprung forth after hundreds of years of gradual societal changes, in the Middle East the situation is quite different. Its violent, secular policy have on the contrary contributed to the rise of extreme religious, political movements such as the one Khomeini led in Iran for example. The same is true when it comes to nations’ disintegrations such as the one in Iraq that has led to our time’s terror-organisations. This is an interesting angle especially in view of the West’s often naïve idea of wanting to export our democratisation processes without taking into consideration other countries’ specificities and traditions (not to mention the greediness of oil exploitations…).

The author ends his chapter by emphasising the importance of theological debates, education, combating poverty and regional demilitarization in order to favour peace and democracy.

The peace-movement’s challenges:

Sofia Walan, the Christian Peace movement’s General Secretary, gets the last words. She encourages the reader to dare to be a positive visionary who discerns the light at the end of the tunnel to keep his dreams alive. However, we’re also encouraged to concretise these in real life with actions such as non-violent education and training. The peace movements also use these in conflict areas.

“Wars are over-financed and peace under-financed with 13% more spent on rearmament and military than on peace and development funding”, she bitterly admits. Isn’t it about time we start to change these figures and we as citizens take our responsibilities and vote for politicians who want to create peace instead of passively live our lives, letting others decide in those important matters? Gandhi’s claim that “the world’s change has to start with each one of us” is as true now as it was then.

Anne Edelstam, Stockholm