One of Paris most frequented museums, shows this winter 2019 a gigantic retrospective in specific style as well as timeframe: cubism (1907- 1917).

Georges Braque, musical instrument, 1908

Thinking that I had seen most of what cubism had to offer, I went to the exhibition a bit cocky but was happily surprised to discover many pieces I had never previously seen. Room after room led to new works of art.

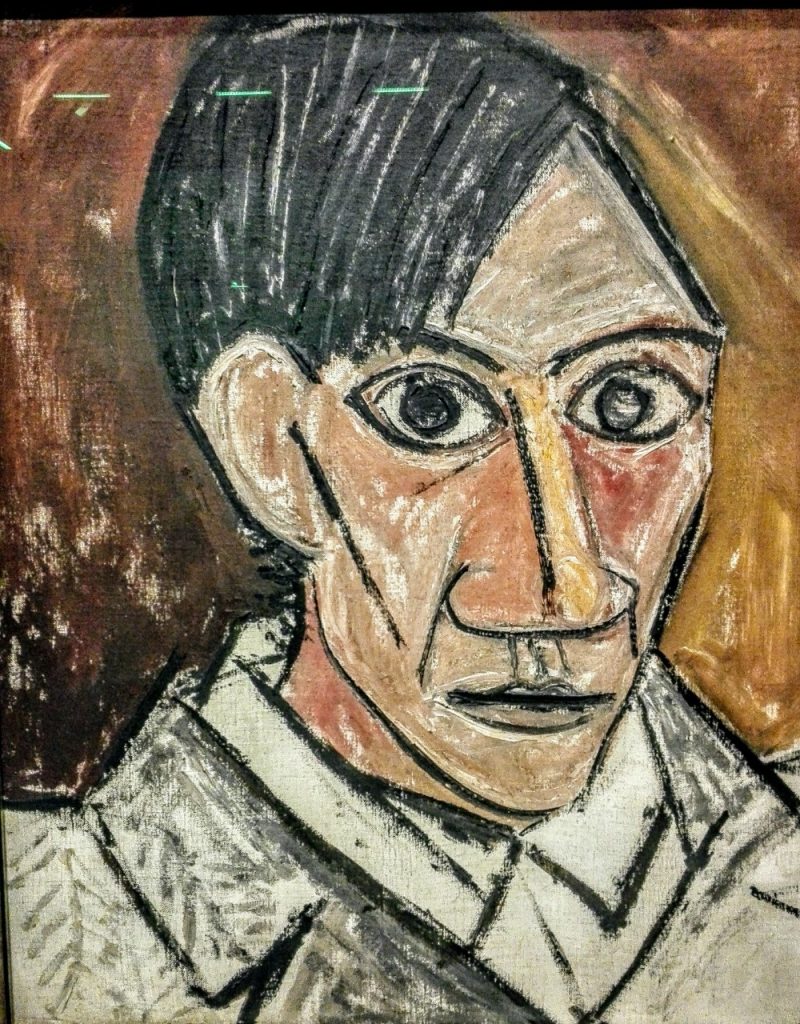

The adventure started in Paris, in 1907, with two young artists: Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso. Nourished by influential artists such as Gauguin and Cézanne, they erased traditional representative art form.

Pablo Picasso, self-portrait, 1907

. Through systematic geometrical abstraction, they invented a new visual and conceptual language. The perspective disappeared and instead the motives were flattened out and superimposed. My thoughts were led to African- and “primitive” arts which also inspired these artists. It was bold to use such styles, as the art scene was quite elitist at the time. I wonder what the bourgeois buyers were whispering to each other when they first laid their eyes on those works of art?

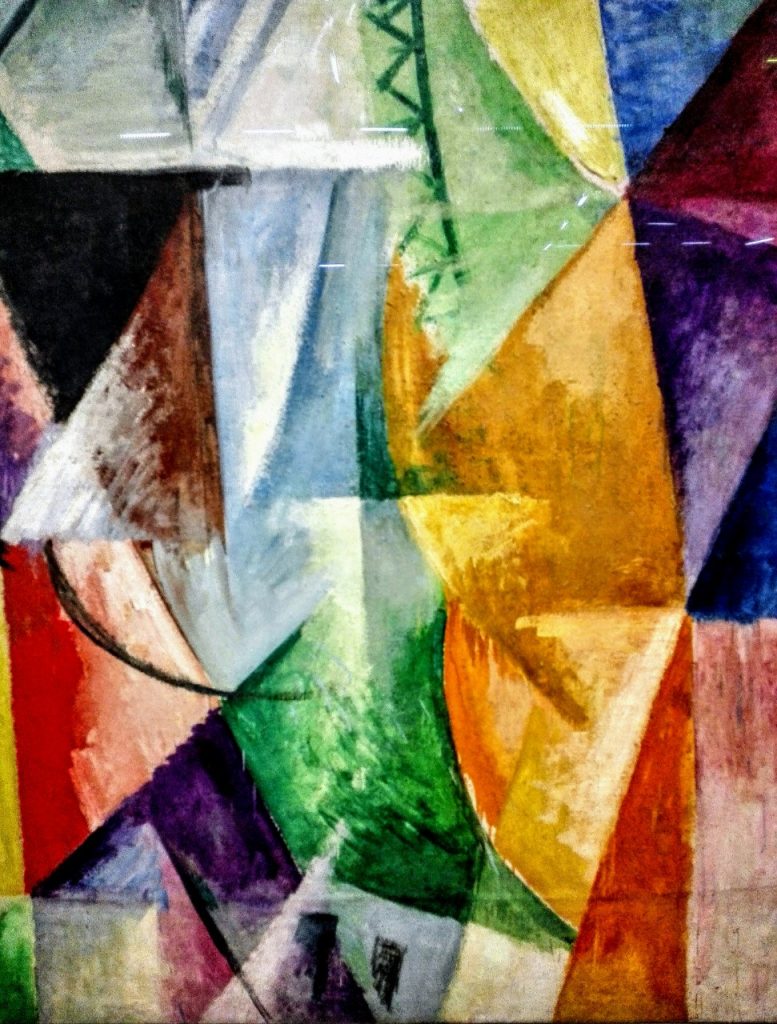

Robert Delaunay, window, 1912.

The materials used in making the art works were also far from noble ones. Instead the artists used whatever they could lay their hands on to do their collages, a technique in itself totally new. They glued, put together, constructed sculptures and paintings with objects others had through in the garbage bin. One might say that they invented recycling before the term became a popular one.

Fernand Léger, houses in the trees, 1914.

If Braque and Picasso started the experiment that later came to be known as cubism, the movement quickly evolved and spread to other artists such as Fernand Léger, Juan Gris and Henri Laurens to name but a few exhibited at Centre Pompidou. Juan Gris called the phenomenon “état d’esprit”, i.e. a mind set.

Already in 1912, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire talked about “a divided cubism”. Cubism developed from more or less entirely black and white paintings, to encompass more and more colours, movement and even at the end rather portrait-like figures.

Marie Laurencin, Appolinaire and their friends, 1909.

Cubism infiltrated both poetry and literature and spread to the finest Parisian salons as well as internationally. As abruptly as it started, it ended in 1917, during WWI. However its influences could be felt during the entire 20th century.

The exhibition is pedagogically conceived. Going from room to room, from 1907 till 1917, the movement’s development with its different painters, sculptors, poets and literature critics was clearly exposed. This retrospective points towards a deep and obviously societal criticism of “law and order” however cubism is somehow “disorganized order”. At the same time, it doesn’t feel out of date, as our contemporary society isn’t that different from theirs. Because even if history never totally repeats itself, mankind doesn’t change over time: the bad comes with the good, darkness with light, black and white with colours and forms with linearity. How it all ends depends on us: what sides in ourselves we decide to feed and in the extension how that is mirrored in the works of art.

How does cubism speak to us? That’s the question this exhibition asks. Each one of us has an answer, or maybe different ones? Go and find out for yourselves at Centre Pompidou.

Francis Picabia, Udnie, 1913