Saint Veronica, 1580, with the veil with the image of the Christ

The Greek painter, Doménikos Theotokópoulos, alias Greco, is one of the world’s most original renaissance painters and masters. He inspired avant-garde artists and impressionists.

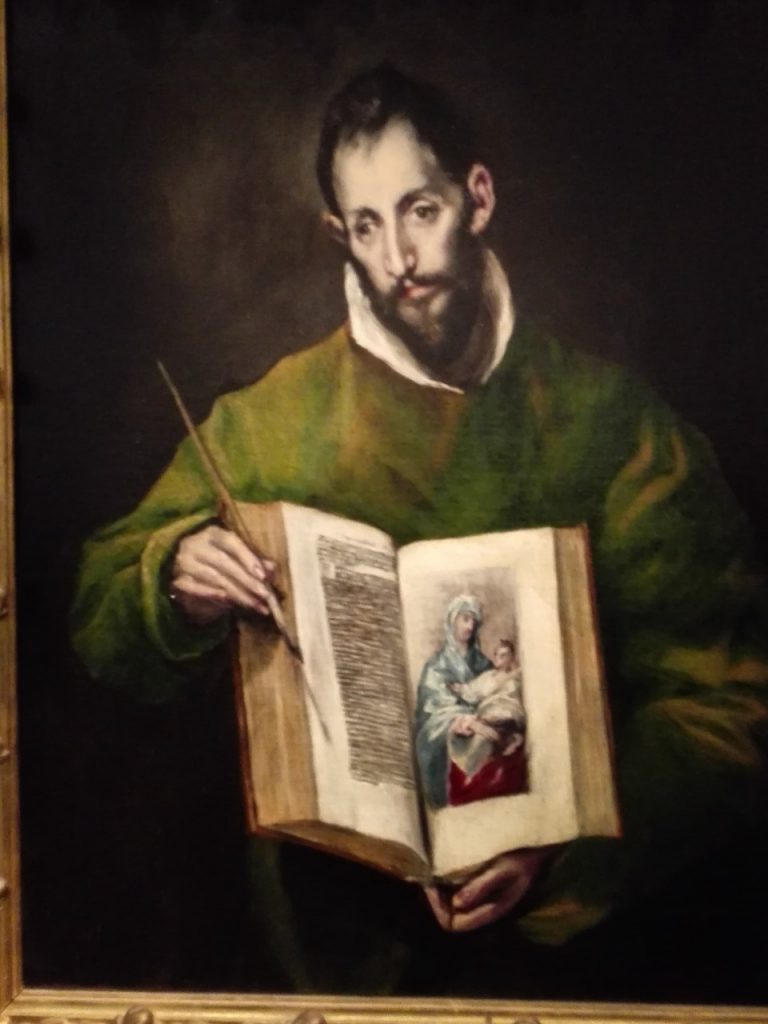

Saint Lucas, 1605

The Grand Palais, in Paris, invites us to an extraordinary exhibition this winter (until 20 February 2020) with 75 masterpieces on display. The queues have circled long to get into the ancient palace to view this wild and unclassifiable genius. However, France has been on strike since nearly two weeks now, with hardly any public transport working, so the affluence to the museums has been rather restricted. It is thus an excellent time to go and see as many exhibitions as possible I discovered, provided one has good walking shoes.

The exhibition’s scenography, with simple white walls, leaves the monopoly on colour to the artist whose palette is explosive! It also gives it a touch of modernity.

Viewing Greco’s elongated figures, reminded me of Giacometti; his flying persons of Chagall; his sometimes very sketchy portraits of the impressionists. I now understand why Greco is called the modernists’ precursor. Despite his predominantly Christine realistic paintings of the 16th century, his prodigy is such that his art doesn’t age.

The Annunciation, 1576.

During these days of Advent, Greco reminds us of why we celebrate Christmas. “A Saviour was born” and with Him: joy as a promise for humankind. Whatever metaphysical thoughts the visitor might – or might not – have, it’s impossible to stay impassable in front of such works of art. The emotions are palpable. The modern painters understood that very well.

However it was more difficult for Greco during his lifetime to get the recognition he so well deserved. After having tried his luck in the highly competitive Venetian market, he moved on to Rome where he perfected his skill at portraits in a personal style, some of which are exposed at the Grand Palais. But it was in Spain that he found his artistic roots and appreciative public, and where he finally settled down.

The Christ chasing the merchants at the Temple, 1575

Toledo, one of Europe’s leading artistic and cultural centres in those days, became the setting for many of Greco’s compositions, consisting mainly of religious scenes. The spread of private devotion led many families to found their own chapels and oratories on top of the orders he got from the Church. One of his best-known series is the one about Christ driving the traders from the temple.

Greco placed painting above all other arts and his colours are as vivid today as they must have been then. There are few drawings that have survived, as he destroyed most of them.

The Saint Family, 1580-85

This exhibition reminds us that a genius, even if he did fall into oblivion for a while, never really dies. Impressionists and avant-garde artists rediscovered him. Cézanne, Chagall and Picasso have lifted him up to be their prophet. And we’re lucky to be able to admire his works, well exhibited in this grandiose palace. Praying to Greco’s God that the strikers will make a halt during the Christmas season, so as many as possible will be able to view this fabulous exhibition. Merry Christmas!

Anne Edelstam, Paris